Can we agree on the facts?

Can we collectively define what we actually know, in a reusable fashion?

Welcome and thank you for joining me in this experiment! I will talk more about why I’m doing this, and what I’m hoping to achieve next week, but I’d love to hear from you. This is designed as a conversation starter.

In most discussions, whether in politics or in research, we tend to jump seamlessly between facts, logical inferences, theories, ideas and value judgments. This can be done manipulatively, but also seems to be “just human”. Are there better ways to reach agreements, and collaborate more effectively? In this issue, I begin with a story of political unrest in Toronto, talk about argument mapping used for both political discourse and literature reviews, and then look at some individuals who are doing interesting work around literature review and fact checking of science.

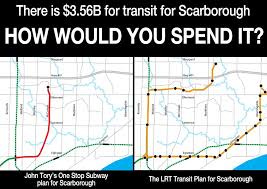

In 2014 I was a PhD student in Toronto, studying how computers can help groups of students to learn, being excited about argument maps and how visual interfaces and interfaces can structure interaction and cognition. At the same time, the city was engulfed in debating whether the ailing rapid transit system in Scarborough should be replaced with a streetcar system, which would reach a much larger area of the very low-density population, or a subway which would be faster, but serve a much smaller population.

This might seem like a debate where you would want the engineers and city planners to carefully map out all of the different costs, projections and consequences. In the end phase, this would still come down to a choice of values, and assumptions – do we think people are willing to transfer, or will they rather take their car, do we think it’s more important to reach a larger population with a slower connection, or a smaller population (but key transfer and consumption points) with a faster connection. Or maybe we should even save taxpayer money, and not extend public transit at all.

However, there were a set of fact that no reasonable person could disagree about (at least not without careful research), which had been presented by city staff after detailed studies, and which should have been able to act as a baseline for a discussion. “Given that it will cost approximately $7Bn for the trains (fact 1), and that expert consensus is that they will last 30 years (fact 2), should we buy them (controversial decision/value judgment)”.

By separating the discussion about the cost of trains (a factual discussion), which should be done with citations, economical models and spreadsheets, from the decision of “given facts we agree on, what is the right decision” (value judgment), we could potentially spend our time getting to the core of the issue.

Instead, what happened was endless confusion, random numbers, contradictions, changing of topic, and general malarkey. I was quite engaged, to the extent of following some of the debates in City Hall live, and it was a frustrating spectacle.

What if we could have mapped out the arguments, and at least gotten a general agreement on the basic facts – wouldn’t that make this discussion much more meaningful for everyone involved?

One possible venue for mapping out the facts and arguments could have been argument maps, which we’ll look at next.

You can argue that the same feeling exists for things like the Brexit-discussions in Britain, the recent Impeachment Trials in the US etc, and be right. However, for me this example is a personal one, and one with less inevitability – there are no real parties in Toronto politics (strangely enough), and as far as I know, there were no groups injecting millions into media campaigns etc. Although people of various persuasions in Toronto had legitimate grievances, as well as prejudice against “urban elites” or “suburban SUV-drivers”, most people wanted what was best for the city, and were not blindly voting for a certain tribal party affiliation.

Literature reviews, “a grand map of the field”

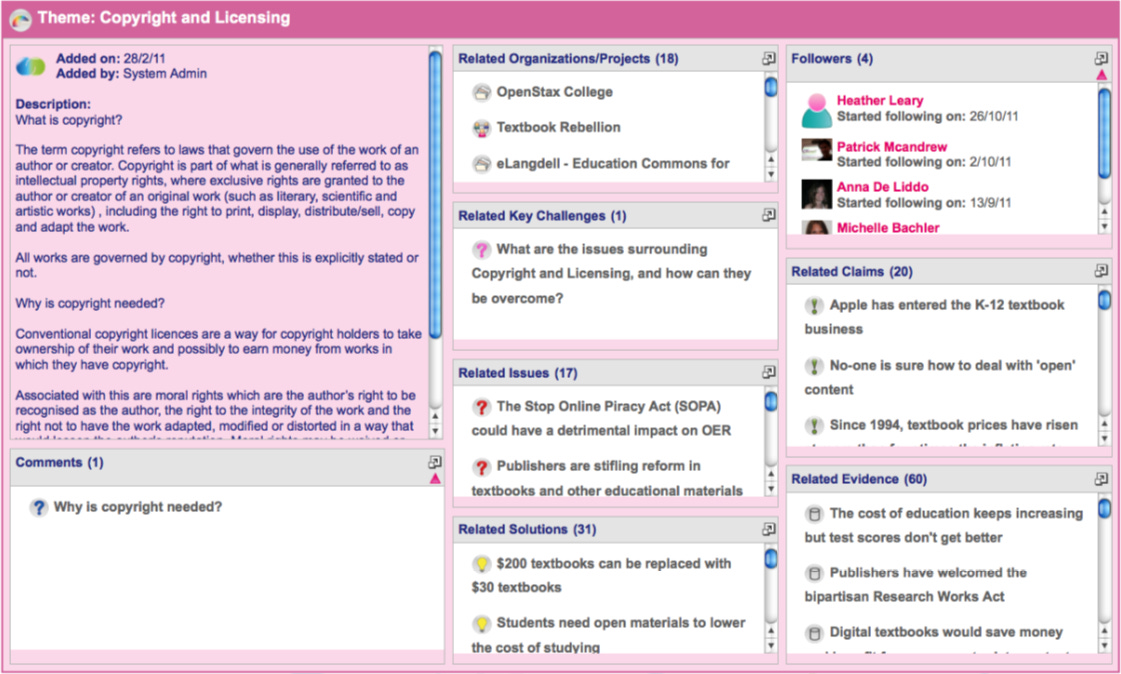

As a young researcher struggling to orient myself in the literature, and seeing papers and research projects that didn’t seem to build on each other, or make any real progress, I really wished we had more coordinated attempts at mapping fields. One such attempt I came across was first mentioned in a grant proposal around Open Educational Resources from CMU and Open University. As one of their outputs, they proposed a research portal.

A research portal. In more established fields such as cancer research, there is a consensus map of the structure of the field, the major research questions, and the different sub-communities and associated methodologies. It is possible to place oneself on the map, and to coordinate effort in a well understood way. […] At various points the OLnet will trigger a series of questions and provide mechanisms to enable those in the field to progress answers to those questions. What is the OER research map? What is the OER design process? What does it mean to validate an OER? What are the central challenges that all agree on? The OPLRN seeks to create a structured 'place' where questions such as these can be debated, and hopefully, enabling more effective coordination of action around issues and OERs of common interest.

This research proposal was a knot in a long thread of research at the Knowledge Media Institute at OU, driven by people like Simon Buckingham-Shum and Anna de Liddo, who worked on an application called Compendium, that traced its roots back to Issue-Based Information Systems from the 1960s. I’ll be diving much deeper into this literature in future issues of this newsletter.

They created a set of Evidence Hubs using Compendium, where people could map out claims, linking to evidence and counter-evidence. Unfortunately, these are now mostly defunct, although you can read about the OER Evidence Hub here. It was a great idea, but did not see the widespread usage they had been hoping for. Perhaps due to the clunky interface, and lack of integration into the normal process of doing research.

This software was also used for civic facilitation, where a trained facilitator would not only take notes, but actively use the representation of collective understanding to guide the group to proceed productively. Here’s one great example, where you can visit all the maps they produced.

This report is a very honest account of the sensemaking journey undertaken by a group of people as they wrestled with a classic wicked problem in environmental planning, which had defied previous attempts at bringing people round the table productively. (Simon Buckingham-Shum)

Another clear example of the necessity for more coordination in mapping out a field came a few years later, with MOOCs:

Literature reviews take 2, “we’re all writing the same review”

In October 2013, Massive Open Online Courses were a fairly new thing, and gaining a lot of interest. Much of this was overblown hype, but there was a sense that underneath, something interesting might just be going on. The MOOC Research Initiative was announced as a series of 20-some small grants with very quick turnaround, generating research that would be presented at a conference (where we ended up stuck in Dallas because of an ice storm).

At University of Toronto, we were lucky enough to win three grants. While working on the proposal and the final report, it struck me how silly it was that all these 20 projects were individually developing their literature reviews. Although each project would of course build on different disciplinary and theoretical foundations, the actual MOOC field was so young that every paper ended up citing the same few sources (including blog posts and newspaper articles).

Wouldn’t it have been better for all of us to create a wikified literature review of MOOC research as a collective undertaking, that we could all link to in our papers?

If the highly structured interfaces for collecting evidence in academic disciplines which I described above didn’t take off, what can we learn from individuals who produce high quality overviews or critiques, and the tools they use?

Impressive feats of literature analysis and fact checking by individuals

I have come across a few personal websites with people who do incredibly meticulous fact checking or organizing of literature. One favorite website is by Gwern – his review of Spaced repetition, for example, is very thorough and a great resource.

Another example is Alexey Guzey’s very thorough review of a book on sleep.

This is a fantastic take-down of a popular scientific book, with very detailed analysis of many of the claims that were made. This take-down has been discussed in a number of fora, and Alexey links to them, and engages actively with any suggestions or critiques. He also explains why he thinks it’s important to not let the book slide by under the guise of “just a popular pop-science book”:

Why We Sleep is not just a popular science book. As I note in the introduction, Walker specifically writes that the book is intended to be scientifically accurate:

[T]his book is intended to serve as a scientifically accurate intervention

Consequently, Walker and other researchers are actively citing the book in academic papers, propagating the information contained in it into the academic literature.

Google Scholar indicates that (a), in the 2 years since the book’s publication, it has been cited more than 100 times.

Alex spent hundreds of hours organizing this review, but will his data be cited in any future studies of sleep? Imagine if he had done this review in some kind of (as yet unspecified) structured semantic format, that allowed for easy reuse?

Better tools for fact checking, and for reusing

Roam is a new note taking app for “networked thoughts”, and the tool and community that inspired me to begin writing this newsletter. One of the most impressive use-cases for Roam is Elizabeth Van Nostrand’s approach to extremely careful reading of history books. She showcased her approach during the San Francisco Roam meetup in January: She will take a history book, for example about the Roman empire, and try to extract every single claim that is made. Things like: The average height in imperial Rome was 164-171 cm for men. I know that I would just pass this by, if I was reading the same book, but she asks herself: How can we know? She looks at the evidence the author presents, follows their citations, but also reads across other sources.

Keeping track of this is complex, but she uses things like tags and block embeds in Roam, which lets her easily filter for all claims from a certain book, all evidence pertaining to a certain claim, etc.

This approach is certainly extreme, both the level of detail spent on a single fact, and that she focuses on facts that don’t seem to be highly controversial or “important” in our lives. However, given the amount of carelessness we see in books, we probably need much more of this kind of deep-dives. And ideally, once we’ve established this very peculiar fact (which is not likely to be featured in Wikipedia), ideally all future publications would directly cite this discussion, and if they have contradictory or supporting evidence, add it to a central repository (or somehow link to it so that they get caught in backlinks), so that we keep building our knowledge.

But if we have all these statements that we cannot be 100% sure about, can we really build any logical tree of inference on top of them?

Bayesian reasoning to the rescue

Right now, Elizabeth’s database, although open, is not hugely useful to the rest of the world, and the Roam technology is far from an interlinked knowledge base. But listening to the interview between Tiago Forte and Conor White-Sullivan (Roam founder), there is no doubt about the ambition to get there. The Roam White Paper (which is somewhat out of date, but describes the initial vision), includes this intriguing piece:

While this is a simple calculation, the strength of Bayesian reasoning is that it breaks down seemingly insurmountable problems into small pieces. Even where no data are available, successive layers of estimates can still provide useful refinements to the confidence levels of various outcomes. By incorporating this framework into the defined relationships between nodes, revisions to the weightings at any point in the network will automatically populate throughout the knowledge graph.

Bayesian probability also provides a framework for decision-making. By estimating the costs and tradeoffs of various options, users can calculate which pathway provides the highest expected value. Again, the quality of the decisions can be refined by successive layers of evidence for and against, even when the weightings are simple estimates of personal preference. An evaluation matrix allows someone to integrate a great deal of information into the final decision, rather than defaulting to simple heuristics.

So perhaps we can imagine a future where we collect evidence, build up a collective base of understanding around specific facts, and build chains of reasoning on top of these facts in a way such that our uncertainty can propagate (and we can recalculate all values once evidence is added to a small building-block). Imagine how a fact such as the average height in Rome could be a small building block for Yuval Noah’s Sapiens. Can we instantly recalculate how damaging it is to his overall argument if evidence is suddenly found showing that all Romans were 2 meters tall?

There are many more issues here to explore, and I look forward to doing so in future newsletters. I would love to hear your thoughts, examples or ideas on any of this. Are there interesting initiatives that I haven’t heard about?

News from the community

After much teasing, Andy Matuschak has shown us his bespoke note taking platform, I will dig into the design and content in a future issue

Conor has promised 100$ discount on a future Roam subscription if you sign up for Nat Eliason’s Roam course.

Twitter list of Tools for thinking people

Beyond Taking Notes (or how I joined the #roamcult) by Tom Hall

(Find notes for this article here. My goal is to add ideas and references that I receive from you, and as I loop back to topics across my newsletter issues, slowly building up a knowledge base around these concepts. You can also leave a comment on Substack).

Thanks to Tom Hall, Vinay Débrou and Dmitriy Fabrikant for early feedback (Dmitriy shared his feedback using another tool for thinking - Knovigator)!

I hate writing literature reviews, although I do see the need to situate one's own work within a larger picture. I really liked Scholarpedia when it started up (http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Main_Page) although it hasn't taken off like I hoped it would. If I had my own way, the literature review section in my article would be a list of URLs.

Do you have any thoughts on what form a literature review might take in a couple of decades from now?

Nice post! I feel that frustration with debates that don't ever start in common ground, and really like the idea of having info tools like argument maps that help collectively reach that ground. I've also been pretty interested in techniques for solving the 'human' part of this problem -- building trust and collaborative engagement on emotionally and politically charged issue-- convergent facilitation is one of the tools I've heard a lot about, which focuses on establishing not just common ground in 'facts' but also in 'needs/values' (see. e.g. http://efficientcollaboration.org/wp-content/uploads/MinnesotaCaseStudy.pdf). One of the complaints about these kinds of processes is the slowness and pain of reaching common ground and moving back up from there, and it's interesting to think how collaboration tech like Roam can help with this. I'm imagining building up a network of info from many different convergent facilitation processes, and using this as a resource to develop a vocabulary of shared values that stretch across many different problem domains (rather than reinventing the wheel each time or relying on the mediator's background).